The #MeToo movement emerged in 2017 in the social media all around the world. Just like in Europe and the Americas, it was not warmly welcomed at beginning in some Muslim countries. However, the internet and social media have been the main instrument for Muslim women to talk freely and anonymously about their experiences of sexual abuse and the inequality they face every day.

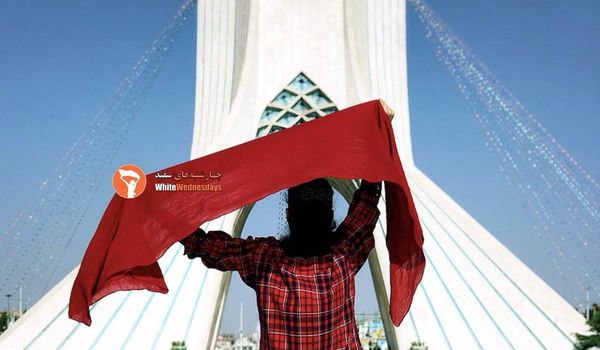

In recent years, there have been numerous media-based movements in Iran, initiated by women, to regain the rights they have lost after the 1979 revolution and to reach equal rights with men in all matters. They protest against forced veiling (Hijab) under the campaign "Women's Stealthy Freedoms in Iran", or "White Wednesdays", when women wear a white scarf showing willingness to have a peaceful discussion about their rights with religious authorities. Both movements set off widespread protests by Iranian women against the gender policies in post-revolutionary Iran, and both emerged through social networks like Instagram.

Discussing women’s issues has been a taboo in many Muslim societies, especially when it comes to sexual harassment. The deep-rooted religious beliefs in most cases point the finger towards victims, blaming them for inciting men through their cloths or behaviors to commit such “sins”. After the Islamic Revolution in Iran, the clergy sought to marginalize Iranian women, to confine them to the home, and to strengthen religious ideas and discourses that would revert back all the progress made under the last Shah on women’s rights. To achieve this, the regime has pursued the policy of presenting Fatemeh, the daughter of the Prophet Mohammad and the wife of Imam Ali (the first Shiite Imam) as a devoted wife and mother. Thereby the regime is imposing a reactionary definition of the ideal woman and implies that women should follow Fatemeh in all their conducts. One aspect of this definition, the decency of Fatemeh, has manifested itself in the separation of men and women in educational spaces.