(1 September 2025) Diana Russell, a pioneer researcher on violence against women, is credited as having popularized the use of the term ‘femicide’ to describe the killing of women because of their gender. She used the term publicly when she testified on the crimes against women during the first International Tribunal on Crimes Against Women held in Belgium in 1976. According to a UN Women report (2024), Africa recorded the highest number of femicide cases in 2023, with an estimated 21,700 deaths. The Initiative for Strategic Litigation (ISLA) is trying to hold states accountable for failure to tackle this crime and is advocating for the inclusion of femicide as a crime within African legal systems.

Naming the unnamed

In May 2025, my seven-year-old niece lost her friend and playmate to femicide. Tamara Blessing Kabura, also seven years old was bright-eyed and just beginning to grasp the world. She was raped, murdered and buried in the perpetrator’s house in Nyeri, Kenya. Her death joins a long, uncounted list of gendered killings in Africa.

Although efforts to combat Gender-based violence (GBV) across Africa have been made, no country in Africa has a standalone law specifically and explicitly defining or criminalizing femicide as a distinct crime in the law. Some countries have taken limited legal or policy steps that acknowledge femicide. However, the law still treats femicide as a personal misfortune rather than a failure of the state.

Globally, different jurisdictions have had varied responses to femicide. Most countries in Latin America have criminalised the gender-related killing of women, either under a legal definition of ‘femicide’ or ‘feminicide’ though definitions and enforcement of the laws vary. The 2009 Cotton field judgement against Mexico was pivotal in shifting from individual prosecution to state responsibility for violence against women. In 2012, Mexico classified femicide as a specific crime within its federal penal code. In March 2025, the Italian government introduced a draft law that gives a legal definition of the crime of femicide and punishes it with life imprisonment. While the bill still needs approval from Parliament, its introduction is a step in the right direction.

The personal is political: when the law kills twice

Generally, the laws in African jurisdictions do not recognise the gendered motivation behind the killing of women and girls. The crime of murder or attempted murder is treated as a gender-neutral crime. Without this distinction, patterns of GBV (e.g.., intimate partner violence, rape, defilement, stalking etc.) are obscured. Consequently, the state cannot be held accountable for the failure to prevent femicide.

If the state of Burundi and Kenya recognised femicide and attempted femicide as a crime, then Francine Nijimbere’s and Jackline Mwende’s husbands would have been charged accordingly. Francine Nijimbere’s husband cut off her arms up to the elbow for failure to give birth to a son in 2004 in Burundi. This was Francine’s second husband and brother-in-law as her first husband had died in 2000, five months after their wedding. Francine had been coerced into the marriage by her in-laws asserting that dowry had already been paid. 12 years later in Kenya, Jackline Mwende suffered the same fate. Her husband chopped off her arms because she was unable to conceive during their seven-year marriage. Jackline’s husband was convicted of attempted murder and sentenced to 30 years in prison. Francine’s husband, however, was only imprisoned for a short time as he was released in 2007 due to a presidential pardon. Francine had to flee her home because the husband had sworn to “finish her off”. Because attempted femicide is not recognised as a crime, the failure of the states to fulfil their obligations under article 4 of the Maputo Protocol is not obvious.

Back in Kenya, the trial of the murder of Ivy Wangechi, a final year medical student in Moi University further reflects the failure of the law to link violence against women as a failure of the state. Throughout the judgement, it is clear that the perpetrator had been stalking the deceased for years in a bid to initiate a romantic relationship with her. However, the deceased was clear that she was uninterested and communicated the same to the perpetrator on multiple occasions. However, the perpetrator was adamant to an extent of using the deceased’s friends to plead his case on his behalf. Eventually, he killed Ivy by striking her with an axe on the head and neck at Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital in Eldoret where Ivy was schooling.

The law as it is in Kenya provides for the ingredients of the crime of murder limiting the act of killing to an isolated act divorced from broader social patterns. By only focusing on whether the person intended to kill (malice aforethought), the law ignores the systemic conditions that allow femicide to recur. Failure of the law to name the killing of women like Ivy as ‘femicide’, is failure to acknowledge a broader pattern of gender-based violence in our societies. Unfortunately, African legal systems are narrowly focused on the motives of the individuals who kill women and girls rather than the gendered systems of power that normalise these murders.

Strategic Litigation as Resistance and Record

All across Africa, feminist lawyers are increasingly using strategic litigation as a tool for social change. Although the perpetrators of femicide are often charged with murder or attempted murder, feminist organisations often use public commentary and amicus briefs where the law allows, to link the murder to a broader culture of misogyny.

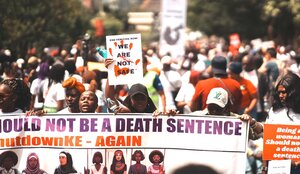

In 2019, the brutal killing of Uyinene Mretyana, a 19-year-old university student from South Africa, sent shockwaves across the country. Uyinene was raped and killed by a post office worker when she went to pick up a parcel at Cape Town post office. Sadly, her death was one of the many women who are sexually assaulted and killed by men in positions of trust and power. Uyinene’s family and feminist activists ensured that the subsequent trial not only secured a conviction but exposed the failure of the state to prevent violence against women. Further, a protest dawning the hashtag, #AmINext, took over Cape Town shortly after Uyinene’s burial, highlighting the government’s inadequacy in protecting women from violence. The pressure led to the National Strategic Plan on Gender-Based Violence and Femicide being established. In 2024, the National Council on Gender-Based Violence and Femicide Act was enacted. The act establishes a council to coordinate efforts in combating GBV and femicide.

Litigation on its own cannot end femicide. However, when feminist lawyers like me litigate strategically in cases where women are murdered, the court room becomes a space for truth-telling. We argue that not only did a man kill a woman or girl, but that the state allowed it to happen. The state failed to prevent the murder by non-reaction to misogyny. The testimonies in court document the number of times the state failed the woman.

Strategic litigation is a powerful tool for holding states accountable in cases of violence against women including femicide. It compels states to confront their failure to protect women and girls from violence. The Cotton field case in Mexico as well as the Uyinene trial in South Africa resulted in legal changes providing for the crime of femicide. When Courts affirm that femicide is not a personal tragedy, but a systemic injustice rooted in state inaction, legal reforms and shifting narratives follow. To prevent femicide, states must urgently (1) invest in social services and prevention programs that address the root causes of GBV, including engaging young men and boys in unpacking patriarchal dominance (2) adopt specific laws on femicide that highlight the gendered nature of woman killing and (3) ensure timely and survivor-centres investigations and prosecutions of femicide cases.