On 5 October 2021, I invited students to curiously await the life-changing news on 7 October 2021, the day the lovers and constant critics of literatures, arts and cultures around the world turned their attention to Stockholm to know the name of the writer-poet – one may now say after Bob Dylan and Louise Glück (2017 and 2020) – who has received the famous ‘call’ from the secretary of the Nobel Prize Committee. This was in the framework of my course ‘Cats, Dogs, Chameleons’? Mapping Literature Nobel Laureates from ‘Africa’.

The literary critic Liyong (2003) used the animal metaphor to review the politics of the Nobel Committee. To him, ‘barking dogs’, mostly ‘Western and European’ had often received the prize, a few chameleons adapting their writing to the market did too, but rarely did ‘regal cat, self-loving or literature-loving cats-sophisticats’, such as the unpredictable Sir Vidiadhar Surajprasad Naipaul, born in Trinidad, receive the prize. What about African writers, such as Chinua Achebe, who Liyong recommended?

African writers: Neither Dogs, Cats nor Chameleons

After the announcement many students and colleagues asked me if I had felt this coming to ‘Africa’ again after Wole Soyinka (English-Nigeria, 1986), Naguib Mahfouz (Arabic-Egypt, 1988), Nadine Gordimer (English-South Africa, 1991), J.M Coetzee (English-South Africa, 2003) and Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s name (Kikuyu-Kenya; Kikuyu is a Bantu language spoken by the Agĩkũyũ of Kenya in the area between Nyeri and Nairobi) having circulated many times for the Literature Nobel? Literary and cultural minds still hope to see Ngũgĩ honoured given his commitment to the promotion of literatures in African languages. He resists the ‘literary identity theft’, which manifests when ‘African voices come out swaddled in European sounds!’ (2021). Where can one place Abdulrazak Gurnah in this spectrum?

From Tanzania, writing in English about Facets of the Human Condition

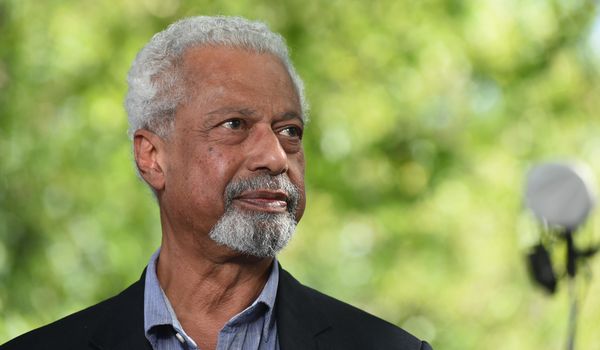

From Memory of Departure (1987) through to Afterlives (2020), Gurnah has written 10 novels, among them Paradise (1994), By the Sea (2001) and Desertion (2005), shortlisted and/or longlisted for significant awards like the Booker Prize. He also wrote many short stories and, until his retirement as a professor of English and postcolonial literature at the University of Kent in 2017, a number of essays, works of criticism and non-fiction: ALL in English.

I had the privilege to tease him during a conference coffee break at the Goethe University Frankfurt am Main in April 2011 by asking: ‘Sir, when shall we expect your works in Swahili?’ His answer: ‘Don’t be silly young man!’ He teased me back although he is very conscious of the language question, with Swahili as a language of primary socialization. This can be seen through words and concepts from Swahili and Arabic that cut across his works, which are sites of memories for the person in exile he has become since 1967, when he left Zanzibar following the Zanzibar Revolution (1964).

Gurnah is hardly known in Tanzania, among other reasons because he does not write in Swahili, his books are too expensive for the average Tanzanian and barely available in Tanzania. Moreover, his books are not part of the school curricula. Nonetheless, the situation will change. Gurnah’s works will now reach the ‘home’ he has never left in his works. As Mkuki Mboya of Mkuki na Nyota publishers (Dar es Salaam) said in an interview with Priya Sippy (2021): ‘It is important for Tanzanians to read Abdulrazak’s work. He covers a lot of the realities of being Tanzanian both at home and overseas […] Often as East Africans, we see the world through other people’s eyes. But with Gurnah, we can also see ourselves.’

Gurnah is a ‘passeur culturel’-mediator-interpreter-(hi)storyteller between continents, which explains the Nobel Prize Committee’s decision to celebrate him ‘for his uncompromising and compassionate penetration of the effects of colonialism and the fate of the refugee in the gulf between cultures and continents.’ Gurnah fully assumes writing in English, which he uses poetically to make African stories, voices and concerns heard. He has used ‘European sounds’ to make some noise for Africans, one might say.

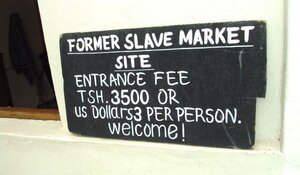

Life in exile – a gift allowing onto take some distance from events – homesickness, home(lessness), (dis)belonging, facing conflictual cultures and identities, desertion, rejection, alienation and loss, racism, the potential of migrants for the receiving societies, the brutality of colonization, (un)expected relationships between colonisers and colonised people, white-black slavery, black-black slavery, independence, statelessness, the disruption of family structures, and the beauty and bitterness of love-life are some topics running through the works of Gurnah who, as I noticed in Frankfurt, enjoys admiring silence.

Silence is my Mother Tongue - Admiring Silence

Silence is my Mother Tongue is the title Sulaiman Addonia (Ethiopia-Eritrea) gave to his second novel (2018). Journeying as a refugee from Eritrea though Sudan, Saudi Arabia, and the United Kingdom before settling down in Belgium, he discovered how silence became his mother tongue. Gurnah, who experienced the trauma of exile, as expressed in many of his novels, has not only written Admiring Silence (1996). He has worked in silence for five decades, patiently, gently and deeply crafting his aesthetics of human exile while reminding how Europeans navigate(d) the world as they wish(ed).

‘Come on, get out of here! Leave me alone!’ is how he described his reaction to the call. Most experts speak of a surprise. I am surprised they are still surprised given the subjectivity and the ‘secrecy’ of the committee’s work. Meyers (2007: 217) ironically reminds that ‘voting records are not kept and the votes and the choices of the academy are as secret as those of the Vatican (the literary world eagerly waits for the puff of smoke from the log-burning Jotul-stove.)’.

Gurnah is neither a dog, a cat nor a chameleon. He, like Daud, the main character of his Pilgrims Way (1988), has been forging his Pilgrims Way and will remain a great mind, a gentle voice, a humble person who thought the call from Mats Malm, the Permanent Secretary of the Swedish Academy Stockholm, was a ‘prank’.

The discussion on language politics, geographical and gender representations has its currency, but to me what counts is the signal the committee sent for the fifth time in 120 years to Africa. Wole Soyinka reportedly commented on the announcement as follows: ‘The Nobel returns home.’

In a year in which other African writers – Tsitsi Dangarembga (Zimbabwe), Paulina Chiziane (Mozambique), Damon Galgut (South Africa), David Diop (Senegal-France), Mbougar Sarr and Bubakar Jóbb (Senegal) – brought ‘home’ major literary awards, it just feels RIGHT that the Literature Nobel Prize winner is, to use the words of another cultural giant from Kenya, ‘a poet of war’. Gurnah is one of the admirable poets-thinkers-observers dedicated to ‘interpret Africa for Africans, trying to interpret Africa for the world, witnesses to history and who are very concerned about what goes on in the wider world’ (Mazrui, 2009). Who’s next? (29 November 2021).